- Home

- Jordan Sonnenblick

The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell Page 2

The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell Read online

Page 2

“JORR-dan!” Mrs. Fisher growls. “Would you like to tell us the Third Rule for Successful and Mature Fourth Graders?”

Sure, I’d love to. But how am I supposed to know what it is with Jennifer Deerfield glistening and sparkling at me?

Robert Falcone, with his back to Mrs. Fisher, tries to mouth the answer to me, but I am not a good lip reader. I shrug because I don’t know what to say or do.

Mrs. Fisher calls on William Feranek, who has helpfully raised his hand.

“Pay attention at all times!” he says confidently.

“VER-ry good, William!” Mrs. Fisher proclaims. Britt Stone smirks at me. I can feel my face turning bright red.

I focus for a moment on the board and see that there are numbers there for seven Rules for Successful and Mature Fourth Graders. I can’t name one, aside from Pay attention at all times. Which I have already messed up before snack break on the first day.

I have a feeling it is going to be a long year.

Last summer, instead of going to day camp at the Jewish Community Center of Staten Island as usual, I decided to go to sleepaway camp in the Pocono Mountains. When I signed up, I didn’t even know where the Pocono Mountains were, but who cared? The camp’s owner, Mr. Kiely, came to my house with a bunch of fancy-looking brochures and a movie projector, and as soon as I saw the black-and-white images of Camp Lenape, I was hooked. The camp was on beautiful Fairview Lake! They had tennis! Sailing! Waterskiing! Archery! Riflery! Minibiking! Hydroplaning!

(I didn’t even know what minibiking and hydroplaning were. I pictured myself riding around the camp on a miniature bicycle like a circus clown and learning to be a pilot. It turned out that minibikes were just small motorcycles—which was way more amazing than clown bikes. Hydroplaning was basically getting pulled around behind a motorboat on a sort of surfboard—less amazing than flying, but not by much.)

Robert Falcone and one of my best friends from outside of school, Peter Friedman, came to camp with me for a month, and so did my sister, Lissa. Well, Robert hated camp. Peter hated camp. Lissa hated camp, just because she was bullied by the other girls in her cabin, got sun poisoning, and got pushed off a cliff into the Delaware River by one of the counselors. She’s pretty picky about things like that.

As for me, I got sun poisoning and food poisoning. I got tonsillitis. I got multiple snake bites. I got into two fights, had an asthma attack, fell off the top of a bunk bed onto the wooden floor of my cabin, learned the hard way that I was allergic to horses, and almost drowned during the quarter-mile swim test when another boy panicked, grabbed my neck, and tried to use me as a flotation device.

It was by far the best four weeks of my life.

At the end, I came home with a new best friend named Hector. Hector is a garter snake. He is the best-looking garter snake I have ever seen. He is mostly black on the top and sides, with a bright yellow stripe down the center of his back. If you hold him up to eye level and look very closely, you can see that just along the bottom edge of his body, where the black part joins the grayish yellow of his belly scales, he has dots of bright red that show every time he inhales. He is also big for a garter snake: nearly two feet long. I caught him during the second week of camp while he was basking in the sun on the shore of the lake, and then kept him in a glass jar filled with grass, moss, and pebbles. Once every few days, I caught some bugs and dropped them into his jar. He seemed to like the bugs, because they always disappeared overnight after I put them in.

Now that he is home and in a beautiful new twenty-gallon aquarium, he has a new diet. When my mom took me to the pet store for the new tank, the guy there told us Hector would be healthier if we fed him fish. So now on Sundays we go to the store and get a plastic bag full of live goldfish. They are ten for a dollar, which seems like an excellent deal to me. When we get home, I pour all the goldfish and their water into a bowl I borrowed from our cat, Spicy. Then Hector sticks his head and the first few inches of his body over the edge of the bowl, and zooms his mouth around and around until he has gulped down two or three of the fish.

Sometimes I invite Peter Friedman over to watch Hector’s feeding time, because it is awesome!

The other good thing about Hector is that he is an excellent listener. When I am sad or worried, I know that I can reach down into Hecky’s aquarium and he will wrap his body around my forearm, stick his head between my thumb and first finger, and look me right in the eye while I tell him all my troubles.

Hector has excellent eye-contact skills. He never gets impatient, and sometimes he flicks his tongue out very quickly several times to show that he is particularly interested. And of course, he can never tell anybody any of my secrets.

Hector is the only one who knows my most important fantasy. In first grade, I got the most important comic book I own: Sons of Origins of Marvel Comics. That’s where I learned how Daredevil, the Man Without Fear, got his powers. When he was just a plain old kid named Matt Murdock, he was walking down the street in New York City and saw an old man stepping into the path of a truck. Anybody else would have been too scared to do anything, or they wouldn’t have thought fast enough even if they had wanted to. But Matt Murdock dove headfirst into the path of the truck and pushed the old guy out of the way! The truck stopped short, but it was carrying radioactive fluid. A tank of the stuff flew off the truck and hit Matt’s head. He went blind but gained the special radar sense that enables him to move around just as well as anybody else. He can even “see” in the dark!

What this has to do with me is that ever since I read it, I have daydreamed about saving somebody’s life so I can be a hero. I have talked this through tons of times with Hector. My perfect injury would be a broken leg, like my mom had when I was little. She got a big, heavy plaster cast that went from the bottom of her foot to the very top of her thigh. It was so heavy that she pretty much had to lie in bed for six weeks. I would love to have that. I’d miss a month and a half of school, and everybody would wait on me like butlers. Plus, I would have a constant stream of visitors who wanted to interview me. I could say things like “It was … nothing. As … long … as the … old man is … okay!”

Even Lissa would have to admit that I wasn’t just some weak little bookworm if I had reporters coming to my bedside all the time.

So I play this game with Hector. “Arm or leg?” I ask him. “Breaking my arm would probably hurt less. But I wouldn’t miss school and I wouldn’t get all my meals in bed.” Hector flicks his tongue out. I don’t know what his answer means exactly. But I’m always glad somebody knows what a hero I am inside.

Especially because I spend a lot of time being afraid. I’m not afraid of breaking a bone or anything like that. My terrible fear isn’t even for myself. I am afraid my mom is going to get killed on the New Jersey Turnpike. Or the Outerbridge Crossing, which is a big bridge that connects Staten Island to New Jersey. Every Monday and Wednesday night, when she drives to Rutgers University in New Brunswick, I can’t stop thinking about this. I know not one but two different kids whose parent died on the way home from New Jersey at night, so it is not like I am crazy. I lie in bed and sweat over this from nine, when the babysitter turns off my light, until eleven thirty, when I hear her key in the front door lock. I don’t tell my mom or dad about this worry. But Hector knows. Hector even knows something worse: Lately, I have been pulling the hairs out of my head while I wait.

If anybody else finds out about that, I won’t be a hero. I’ll just be some kid who has to see a psychiatrist every week. And that would be the worst, because my father is a psychiatrist. This has to stay between Hector and me.

* * *

By the end of the first week of school, I have tons of new things to share with Hector.

“Can you believe Mrs. Fisher called me obstreperous?” I ask him. “First of all, I had to look it up in the dictionary. Second of all, she is wrong. I am not noisy and difficult to control. She’s just mean and boring. Who wants to pay attention to someone who calls you CHILL-dre

n every three seconds, anyway?”

Hector flicks his tongue out. He understands.

“And it gets worse! She yells at me because she says I can’t sit still! But that makes me nervous, and then I really can’t sit still. Plus, I don’t know what she expects me to do with myself when I finish my work early. She yells at me if I read a book under my desk, too. And if I daydream. What am I supposed to do, just sit there and pretend to be a statue?”

Hector doesn’t move. He just looks at me from between my fingers, like a very attentive sculpture of a snake. Maybe he should be in Mrs. Fisher’s class instead of me.

Wait—that gives me a brilliant idea! I will ask Mrs. Fisher if I can bring Hector in for Show and Tell. I will tell her it is scientific. She hasn’t done any science lessons with us so far, but there is a long, high table at the back of the classroom with all kinds of old projects on it, plus lots of nature-related stuff like dried leaves, collections of pine cones, and even a few rocks that look like they might have fossils inside. Maybe she likes animals. I can mention to her that my Grandpa Sol used to be a biologist. When she hears that, and sees how responsible I am with Hecky, and finds out how much I know about snakes, maybe she will see I’m not just some squirmy troublemaker.

I’m a squirmy troublemaker with a cool pet.

Ever since I started taking all my asthma medicines last spring, I have had a lot of trouble sitting still. I keep getting in trouble for tapping on things! My mom has decided I should try taking drum lessons, because she says it might help me focus my energy. I don’t care about focusing my energy—I just think playing drums might make me cool.

I have no idea what a drum lesson is going to be like. I hope it isn’t going to be a complete failure like my first and only guitar lesson, because all I got out of that was a bunch of blisters on my fingers and a total hatred of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” All I know is that whenever I see a live band playing at a wedding, a family bar mitzvah, or anywhere, I just want to stand by the drummer and watch everything he does. Drummers seem like gods. They move faster than anybody else in the band. Their hands go so fast that sometimes the drumsticks become nothing but a blur in the air! Drummers are powerful. They have control of the whole band. At the beginning of every song, nobody can do anything until the drummer says, “One! Two! Three! Four!” The coolest drummers don’t even say it out loud. They just click their sticks together to give everybody the beat, and then the whole band comes in perfectly together. It’s almost like magic. If I were the drummer on a stage, I wouldn’t be afraid of anything, not even getting yelled at by Mrs. Fisher, because if anybody tried to yell at me, I would just hit all my drums and cymbals as fast as I could. And then none of the yelling would even reach me.

I went to a wedding in Brooklyn last spring, and the drummer was the coolest person I’ve ever seen. He had long curly hair, and when he played fast, it flew all over the place. When the stage lights hit him, you could even see drops of sweat flying off the ends. But the best thing was the first time the band played a slow song. At the beginning, he didn’t do the shouting-numbers thing, and he didn’t bang his sticks together, either. The whole band turned to look at him, and he frowned a little bit and waved one of his hands slowly through the air for a while like he was conducting an imaginary marching band. After maybe ten seconds, a couple of the other men nodded at him and smiled, so he turned his head in a little half circle to make sure all the musicians were still looking at him, and whispered, “One-two-three-four-one-two …”

When the whole group started playing, all the drummer did at first was use his right hand to play one cymbal, very softly, to keep the beat. And that was all he had to do to control everything that was happening on the stage. I could feel it. He was controlling the speed of the song and telling everybody that they needed to play quietly, all at the same time. With one hand and one stick! His eyes were closed, and he nodded along in time to the music for a while. Then he opened his eyes, caught me looking at him, reached down and a bit backward with his left hand, picked up a tall glass full of ice and some dark liquid, and winked at me as he took a sip. After a little while, he put the drink back behind him, picked up his other drumstick from where he had laid it across the top of one of his drums, and used both hands to lead the band into the loud part of the song.

He was so casual about all of it! Like, Oh, I’m just relaxing up here, being the boss of all these professional musicians, making the grown-ups get up and dance, and—while I’m at it—grabbing a few refreshing sips of my favorite beverage. No rush, I have at least twenty seconds until the big exciting part of the song.

I wanted to be casual like that. Because then nothing would bother me.

I spent maybe half the party just standing there and watching. When the band stopped for a break, I wanted to say hi to the drummer, and maybe ask him how he had started playing. But I was too shy. So I just kind of faded away from the edge of the bandstand until I got back to the tables.

Anyway, I don’t know how I can learn to be that guy from a few lessons. I am only a shrimpy, nervous fourth grader. It seems to me that becoming a drummer isn’t just learning a set of skills. Becoming that guy would be more like a transformation: caterpillar me would have to somehow turn into … not a butterfly, exactly. Something cooler and stronger. Something heroic. Like a lion. Or Robert Falcone, but with drumsticks.

That’s what I want from drum lessons. To become a legend in just thirty minutes a week.

* * *

When I meet my teacher, Mr. Fred Stoll, I’m not so sure this is going to work. Mr. Stoll is a thin man, a bit younger than my parents, with short, neatly cut blond hair and a very soft voice.

“Call me Fred,” he tells my mom with a smile as he lets us into his house down by the ferry terminal. “And this is my wife, Jottie.” The wife, a pretty hippie lady with dark frizzy hair and a friendly grin, offers my mother something called “herbal tea.”

This man doesn’t look like a rocking drummer. He looks like a dad. His name is Fred. He has a wife. Who makes people weird kinds of tea in the middle of the afternoon. How is he supposed to teach me to unleash my inner cool guy?

He leads me down a dark, dusty flight of stairs to his basement while Jottie is busy introducing my mother to their three cats.

Seriously, cats? How rocking can cats be? He should have boa constrictors, at the very least. Possibly cobras.

At the bottom of the stairs, though, is the best room I have seen in my life.

It’s like a secret drum lair. There is a blue-sparkle drum set squeezed in on one side, with a record player next to it. Then there is a workbench with drum cases stacked up all over it, and below the bench are lines and lines of record albums—easily the largest collection I have ever seen outside of a music store. The whole room, from wall to wall, is nothing but drums and music.

Maybe Mr. Fred Stoll is like Batman or Superman. People in the upstairs world think of him as a mild-mannered, cat-owning husband. But once you are allowed into his DRUM CAVE, you see the truth behind the disguise.

He sits down at a stool next to the drum set and gestures for me to pass him and sit on the stool that is actually set up directly in front of the drums—the stool a real drummer would sit on to play this set!

When I sit down, I am kind of excited and also kind of terrified. I want so badly to be able to sit right here and make amazing, thunderous noise, but I don’t even know how to hold a drumstick. Fortunately, that is the first lesson. Mr. Stoll lays two sticks down on the shallow, wide drum between my legs and says, “Lesson one: Pick those up.” I want to ask him how I am supposed to pick them up, but I feel like this is some kind of test.

Mr. Stoll is Obi-Wan Kenobi, I am Luke Skywalker, and I am supposed to use the Force to lift the sticks.

I grab a stick in each hand, gripping them tightly like clubs. Mr. Stoll says, “Okay, watch me,” and picks up a second pair of sticks that he has placed on his lap. “See how I’m barely squeezing them at all? You ju

st want to put your hand over the stick, palm down, and then gently grasp it. Most of the pressure should be between your thumb and your pointer finger. Some drummers hold their left stick in something called a traditional grip, but you want to learn to play the drum set, right?”

I nod.

“Well, if you want to play the most current music, I think that the grip I’m going to show you makes the most sense, then. It’s called matched grip, and it will make things easier as your hands are moving around the set. Okay?”

I nod again. Clearly, if learning to hold the drumsticks is going to be a whole big challenge, I want to keep it as simple as possible.

“Put the sticks down on the drum one more time. Now pick them up again, gently. You should be able to control the stick with just those two fingers.”

This time, I pick up the sticks as though they are made of eggshells. Mr. Stoll smiles, very slightly, and says, “Now hit something.”

It’s only the second week of school, and Mrs. Fisher has already noticed that my handwriting is not neat. By not neat, I mean it looks like a dying chicken dragged a pencil across the page because it was stapled to his leg.

And that’s when I print. You should see my cursive.

It doesn’t matter that she’s right. What matters is that she compares me to William Feranek in front of the whole class.

“JORR-dan! This spelling paper is sloppy! I will not accept messy work!” I try to tell her that I spelled every word right, but she doesn’t care. “Nobody cares,” she purrs, “if you’ve spelled the words right if nobody can read them. Perhaps you should try to be more like William. William Feranek has perfect penmanship!”

Curveball: The Year I Lost My Grip

Curveball: The Year I Lost My Grip Dodger for Sale

Dodger for Sale Are You Experienced?

Are You Experienced? Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie

Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie Dodger and Me

Dodger and Me The Secret Sheriff of Sixth Grade

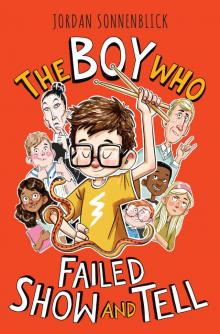

The Secret Sheriff of Sixth Grade The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell

The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie

Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie Dodger for President

Dodger for President Notes From the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver After Ever After

After Ever After Zen and the Art of Faking It

Zen and the Art of Faking It Falling Over Sideways

Falling Over Sideways