- Home

- Jordan Sonnenblick

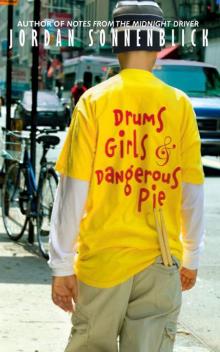

Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie Page 3

Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie Read online

Page 3

Then Grampa nosed his huge Chevy Impala into a parking space at the hospital. By the time we got upstairs to the maternity ward, and I saw the balloons, the flowers everywhere, and my three other grandparents crowded around an incubator crying and smiling like they’d just won the Powerball Lotto, I was having second thoughts about this whole “protector” gig.

Still, though, I have always protected Jeffrey. When he was three and fell on a stick in our driveway, I was the one who took him inside and got a Band-Aid and his boo-boo bunny. When his little best friend, Alex, tried to push him off of the swing set last year, I got in trouble for pulling Alex down and screaming in his face until my mom dragged me away. Even when Jeffrey had a big asthma attack and had to be hospitalized overnight when he was one, I stood right next to his bed and held his hand for what seemed like hours and hours until he fell asleep. Then in the middle of the night when he woke up scared, I crawled into his bed with him, and our parents found us that way in the morning.

I haven’t always liked being the Protector, but I think I have taken the job pretty seriously overall.

So how come when I wasn’t looking, Jeffy got cancer?

The journal topic that day, I later learned, was “Discuss your favorite character in Huckleberry Finn.”

The thing I couldn’t believe was how this cancer thing turned the whole planet upside down in one day. I mean, it turns out that Jeffrey had to have been sick for a while without us knowing it. When my mom got him to the emergency room and the nurse took his temperature, it was a little over a hundred. The nurse asked him how he felt, and he told her that he knew he had a fever and that his “parts” had been hurting for a long time. Meanwhile, his nose just kept bleeding and bleeding. The regular E.R. doctor must have thought this looked a bit unusual, so he called in a pediatrician. My mom told us that night that she couldn’t believe what the pediatrician told Jeffrey to do next: “Please walk over to the desk there and get me a tissue.” My mom was thinking, “My child is BLEEDING PROFUSELY and you want HIM to get YOU a tissue?” But Jeffrey got right up and started walking toward the main desk of the E.R. My mom said she suddenly noticed that Jeffrey was limping. As she told us this, after Jeffrey was already upstairs in bed, she started to weep.

How did I not notice this? Why did I need a doctor to show me? How long has he been limping? How long has my baby been limping around with a fever while I was too busy grading papers and making dinner to even LOOK at my Jeffy?

My dad, who wasn’t looking too composed either, came over and put his arm around her. He didn’t say anything, though, so I chimed in.

Mom, we were ALL too busy to notice. It’s not just you. He even told me this morning that he was cold and his parts hurt, and I just thought he was Jeffrey being Jeffrey. I was bummed that he interrupted my practicing to ask for breakfast. My own brother…and all he wanted was some oatmeal.

Now I was getting, truthfully, a bit weepy myself. See what I mean about cancer turning everything upside down? This pity festival went on for at least another hour, with each of us pretty much just saying over and over that this was somehow our fault. Now, let’s face it—I’m smart enough to know logically that Jeffrey didn’t get sick because I stole change from his piggy bank when he was three and bought Tic Tacs for my whole class with it. But for some reason on that first horrible night, it seemed as though everything I ever did to Jeffrey had probably caused some horrible genetic damage.

And now there we were, confessing our sins.

Finally, I asked my parents what was going to happen next. They told me that my mom would be taking Jeffy to Philadelphia, an hour and a half away, first thing in the morning, for some medical tests.

So he might not even have cancer, right? If the experts are in Philly, these local doctors are probably wrong pretty often. And then tomorrow night, you’ll come back, right? And you’ll tell us it was a mistake?

My dad chimed in, Anything’s possible, son.

But Mom wasn’t in a mood for optimism. We won’t be coming back tomorrow night, Steven.

What do you mean you won’t be coming back tomorrow night? What about Jeffrey’s school? If he misses two days of kindergarten in a row, he’ll probably miss, like, a whole letter of the alphabet. And what if it’s a vowel? Then he’ll have this huge problem with reading. He’ll read, “The fat cat sat,” but he’ll think it says, “The ft ct st.”

Very funny, Steven.

And what about your work, Mom?

Both of my parents got really, really quiet all of a sudden, and I knew this was not a good sign.

Finally, my dad spoke. Mom might not be working for a while.

But what? But why? How did…?

Steven, I had a long talk with my principal today. There’s a pretty good chance I’ll be taking some time off of work.

Wow, Mom, you were pretty busy today.

She looked away.

I guess because I was nervous, I started to recap the day’s events out loud. So OK, here’s October 7th with the Alper family. Wake up as normal people. Younger son gets nosebleed. Older son goes to school. Dad goes to work. Younger son goes to emergency room. Younger son allegedly has cancer. Mom quits job. Mom and younger son get ready to skip town. Father and older son stand around like idiots and prepare to buy a huge supply of—what? TV dinners?

Please calm down, Steven. We are all going to have a big adjustment to make.

Adjustment? ADJUSTMENT? Getting a new car is an adjustment. Switching math classes is an adjustment. Finding out your brother has leukemia—supposedly—and that your mom is now unemployed and that they’re running off to the city in the morning, leaving you and your father to starve to death alone, is not an adjustment.

Steven! This isn’t about you. How do you think your brother feels right now?

Then we had another one of these new, despairing silences. Until I had to ask a question that somehow hadn’t occurred to me. Ummm…Mom? How much does Jeffy know?

It turned out that Jeffrey knew he might be pretty sick—try cauterizing a kid’s gushing nose with a heat gun without him figuring out that something is up—but didn’t understand too much about the details. My mom hadn’t wanted to worry him prematurely. When she told him that he would have to go with her to the big city in the morning to see another doctor, all he had asked was, “Will Steven come, too?”

This was the one piece of information that put me over the edge. I started crying, but when my mom started coming over to hug me, I ran upstairs for bed. If I had known that this would basically be the last time I’d have both parents paying attention to me at once, I probably would have taken the hug.

I could hear my parents talking for a long, long time before I fell asleep, but nobody came up to check on me. Jeffy groaned in his sleep once or twice in the next room but never woke up. I was alone. I counted the little glowing stars on my ceiling, revisited my argument with Annette, played drum beats on a huge imaginary drum set in my head, and then realized one last thing I hadn’t thought about since I’d walked in the door after school.

And I muttered to myself in the darkness, Guess what, Mom? I’m going to be the star of my spring concert.

JEFFREY’S VACATION

In the morning, I was the first one up, as usual. I was really hungry, for some odd reason, and I was thinking that Jeffrey was going to have a hard day. So I decided to surprise him with the oatmeal he had never gotten the day before. I got everything all cooked up and had just covered the pot when I heard little footsteps behind me.

I started to speak and turn at the same time, Good morning, Jeffy. I made you some…

Now, I knew Jeffrey was bruised up from his fall, and I also knew that bruises always look worse on the second day. But at that stage of the game, I didn’t know how much worse bruises look on a kid with leukemia. When I turned around, I gasped and my hand came up to my mouth. Jeffrey had the two worst black eyes I’d ever seen, and his nose was swollen to about twice its normal size. He saw my reaction an

d winced.

What’s wrong, Steven?

How does your face feel, Jeffy?

It feels thick.

Thick?

And hot. Why?

It’s, ummm, a little swollen.

What do you mean? Do I look funny? What if the new doctor thinks I look stupid? I’m going to go look in the mirror.

Before I could even think of stopping him, he ran to the foyer and looked in our hallway mirror. I ran over, and he looked at me with horror in his eyes.

Steven, I look like a raccoon.

You do NOT look like a raccoon.

Actually, he looked like some deranged anteater, but I didn’t figure that would be the thing to tell him.

Yes, I do. Oh, no. What if I stay this way forever?

You’re not going to stay that way forever, Jeffy. People get black eyes all the time. If they never got better, the streets would be crowded with raccoon people. Soon, the raccoon people would find each other and breed.

I was on a roll here.

The preschools would fill up with strange ring-eyed children. Soon the raccoons would be taking over our streets, stealing from our garbage cans, leaving eerie trails of Dinty Moore beef stew cans in their wake. Gangs of them would haunt the malls, buying up all the black-and-gray-striped sportswear. THE RIVERS WOULD RISE! THE VALLEYS WOULD RUN WITH…

Steven, you’re joking, right? What’s for breakfast?

Oatmeal.

Yay! Moatmeal!

And just like that, Jeffrey was over his crisis. Which is pretty amazing. If I have a single zit, I want to crawl under my bed and hide with three days’ worth of food. This kid looks like he just lost a boxing match with a gorilla, and it takes him, like, five minutes and a bowl of hot cereal to forget about it.

While Jeffrey was eating, I snuck upstairs to warn the ’rents about Jeffrey’s looks. I figured my mom was going to have enough shocks to deal with, so I should spare her this one if I could. It worked, or at least the ’rents managed to hide their reactions from Jeffrey when they came downstairs. We all sat at the breakfast table, pretending to be normal and cheerful. But you know how when you watch the Brady Bunch, you think, “Oh, come on! Nobody is this happy. What’s wrong with you people? And who picks out your CLOTHES?” Well, breakfast was sort of like that, only instead of the clothing problem, we had an unmentionable cancer problem.

The good-byes were pretty uneventful, and Jeffrey even managed to bug me, which was probably a good sign.

On his way out the door, he turned to make fun of his brother. You’re going to schoo…oooo…llll. You’re going to schhhooo…ooooo…lllll.

If he had known what was coming up for his day, he would have been begging me to smuggle him to school in my backpack.

Once my mom and Jeffy left, my dad and I just kind of slid around the house, getting ready to face the day, not quite ready to face each other. We got into the car without word one being spoken, and on the actual ride, it was so quiet between us that I imagined I could hear the tire treads rubbing against the road. I couldn’t wait to hop out of there and get into school, but somehow when we did pull up to the building, I didn’t make any move to get out. My dad nearly looked at me, and I kind of stared through his right shoulder. After about a minute of this, we both mumbled at once, Well…OK…

That was the deepest conversation we would have all week. I got out and went to school. When I came around the corner toward homeroom, I saw Renee and forgot about everything else. She was wearing this shirt that was clingy and shiny and maybe a little bit see-through, with a skirt that just wasn’t quite doing its whole job. I stopped and stared for far too long, until Annette banged my arm.

Check HER out. There’s no way that doesn’t violate the dress code! I hope she gets marched to the office. It’s disgusting! Don’t you think so, Steven? Steven? Ssstteeee…vvvveeeeennnnn?

So at least Annette was talking to me again. When I tore my eyes away from Renee, the contrast was pretty strong.

Annette was doing the 1970s retro thing, I guess. She had on this sweater that was pretty tough to describe. It looked like what you’d get if all of your parents’ favorite dinosaur-rock bands died and left you all their extra fabric, and then a little old blind lady sewed all the pieces together with a tasteful burnt-orange thread. It made a statement, though. It truly did.

Uuhhhh, yeah. Sure.

Oh my God, I almost forgot! Steven, how’s your brother? Did you get in trouble?

I didn’t get in trouble. And he’s…fine. I’m sorry I yelled at you on the bus.

I’m sorry, too, Steven. I know how much you care about your brother, and you must have been worried.

Me, worried? Maybe. You might notice that this would have been the perfect time to tell Annette the whole story, but for some reason I didn’t want anyone at school to know. It turned out that once I decided not to tell Annette at that moment, it became almost impossible to tell anybody. So for the rest of the week, while I was walking around in a fog, I didn’t say a word. I joked around with my friends, played the drums, sat in classes, and acted even more lame than usual around Renee, but I didn’t let anybody know what was going on with Jeffrey.

It was weird. The longer I pretended everything was normal at school, the more I believed everything was normal. I started thinking over and over again, “Doctors are wrong all the time. You hear about these malpractice things every day where people get medicine that’s not even theirs. I bet Jeffy’s down there in Philly, guzzling cheesesteaks, having a great time, getting waited on hand and foot by Mom, while I’m up here eating all the Hungry Man dinners on the East Coast, and Dad is pretending I’m some odd thirteen-year-old stranger who’s just moved in to keep the microwave warm while his REAL family is away.”

Meanwhile, that wasn’t quite the way things were actually happening. I found out later that my dad was getting horrible phone reports from my mom for an hour each night, long after Jeffy and I were both asleep. So, in a sense, my dad was shielding me by not talking. I could have used some companionship that week, but maybe I wouldn’t have believed anything about Jeffy until I was ready, no matter what Dad said.

The week went by in this half-awake sort of way, for me at least. While I was staring at Renee in fifth-period math and praying nobody would make her change her outfit, Jeffrey was getting strapped down to a gurney. While Annette was smacking my arm yet again, a doctor was shoving a huge needle through Jeffrey’s back into his hip, all the way into the bone. While I was laughing at some joke the teacher hadn’t heard, Jeffrey was screaming as the needle sucked the bone marrow out of him. But I was just thinking about me and about how ridiculous it was that everyone except me was getting so freaked out over a stupid bloody nose.

The only times all week when I truly felt all right were the times when I was playing the drums. I have always been pretty serious about hitting the old practice pad at home, but now that I was living in the Conversation-Free TV-Dinner Zombie Zone, I basically had nothing else to do. It was truly ridiculous—within days after Jeffrey’s fall, I got to the point where I was spending twenty-five minutes a night playing double-stroke rolls on the surface of a dime without missing or even moving the coin. I knew my drum teacher, Mr. Stoll, was going to be pretty impressed with my progress. Before this, he had assigned me maybe two pages in each of three different exercise books every week. But now I was doing two pages per NIGHT in each book. I was also practicing for my upcoming conga drum stardom. Mr. Watras lent me a pair of really expensive bongos to use at home, along with a huge stack of ancient Latin jazz records. He had even called Mr. Stoll (they had played in bands together—isn’t it weird when grown-ups have actual lives?) to tell him what I should practice on them. Fortunately, my dad has a Stone Age stereo system in the basement with an actual turntable, so I was playing along with at least one whole Latin record each night.

I know, I know, you’re probably thinking that my new superhuman drum schedule must have been cutting into my homework time. And in

fact you would be correct, except that I completely stopped doing homework the day Jeffrey got sick and didn’t start again until I got busted by my teachers much, much later. I sometimes looked at my homework assignments and occasionally even wrote a heading on a piece of paper as if I was about to attempt the work, but somehow I wound up going to school empty-handed day after day. In class, too, I just started basically blanking out every period, every day.

You might also think that lots of my friends would notice it if their pal Steven stopped doing schoolwork, started staring off into space 85% of the time, and suddenly avoided any mention of his family. But you’d be wrong there. I think every group of friends has a “guy” for each different function—like the “sympathetic guy,” the “funny guy,” the “jock,” the “guy who gets picked on.” I had never really thought about it before, but apparently to my friends I had two roles: “funny guy” and “drum guy.” So as long as I carried a pair of sticks and kept the humor coming, nobody was going to guess anything was up with me.

Except Annette. Pretty much every morning in homeroom, she would ask me what was wrong. The first few days, I would make a joke or say that nothing was the matter. After that, I got more and more impatient with her every time she asked. I kept hoping that if I was just snappish enough, she would leave me alone. Meanwhile, she stuck with me. She was my best friend—maybe my only true friend—but I wasn’t seeing it.

There was only one way I was communicating with the outside world at all, and that was my English journal. Miss Palma has this rule that if you fold down your page, it shows your journal is private. Well, my journal was starting to look like some kind of weird origami factory, with page after page folded on different angles and edges sticking out all over the place. Of course, Miss Palma had to know that I was doing something strange, because again and again I’d be writing three and four pages, supposedly about these completely impersonal topics, and then folding down all the pages one by one. But either she really believed I was having deep emotional reactions to questions like, “Should our school have uniforms?” or she was just giving me enough rope to hang myself.

Curveball: The Year I Lost My Grip

Curveball: The Year I Lost My Grip Dodger for Sale

Dodger for Sale Are You Experienced?

Are You Experienced? Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie

Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie Dodger and Me

Dodger and Me The Secret Sheriff of Sixth Grade

The Secret Sheriff of Sixth Grade The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell

The Boy Who Failed Show and Tell Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie

Drums, Girls, and Dangerous Pie Dodger for President

Dodger for President Notes From the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver After Ever After

After Ever After Zen and the Art of Faking It

Zen and the Art of Faking It Falling Over Sideways

Falling Over Sideways